CHAPTER XXI

WE BREAK THROUGH!

All day our artillery had kept up an intense fire on the German lines. Fresh regiments from our corps replaced the ones depleted by the previous attack.

Engineer battalions worked all day in the forest, felling trees and cutting the logs into pieces suitable for bridge building. Should the attack prove successful, it would be necessary to rebuild the three bridges that led across the marsh.

These timbers were carried to the edge of the forest by the road, under the protection of the screening trees, and were placed in regular order so that no confusion would result if it became necessary to put them in place at night when all of the work would have to be done in darkness, for the enemy commanded the road from their position on the sand-hills.

At ten o'clock our Siberians made a terrific attack, wave after wave of men being sent over the marsh in the face of a devastating fire from German machine-guns, rifles and artillery.

Despite their enormous losses they stormed the Austro-German positions, carrying all three lines of defense and driving them back to the depth of five meters beyond the river.

Attacks were carried out all along the lines for the distance of twenty kilometers, but our corps was the only one to penetrate the German positions. The result was that both flanks failed to advance and an extremely difficult problem developed.

Our men were across the river and consolidating their lines four miles back from the stream in the center. From this point our position sloped back in a curving line toward either flank where the supporting troops had failed to cross the river. In other words, we had penetrated on a six-mile front to a depth of four miles at the deepest point, forming a nasty salient open to a flanking fire from the Austro-German guns.

Running through the center of this salient was the single road through which all supplies to the advanced lines had to be carried. The wounded also had to be brought over this road. As it was raised above the level of the flat marsh, standing out in plain view of the enemy observers, anything attempting to cross was under their direct fire.

The engineer battalion rushed up bridge parts, and by the time the first streaks of dawn appeared in the east, we received word the bridges were completed.

The commander of the fourth regiment, which was holding the extreme end of the salient across the river, called up by telephone asking us to move our dressing station up as nearly as possible to the newly established first-line and to bring some ambulances over as soon as possible, for there were hundreds of wounded lying about in the fields.

I accordingly ordered five ambulances and a wagon carrying supplies to be in readiness to start across the road for the other side, and Metia and I rode ahead to pick out the location for this advanced dressing station.

As we came to the edge of the forest and looked out over the road we saw that it was a spouting lane of flying dirt and smoke from the German shells where they were trying to destroy the newly constructed bridges and to wreck the surface of the road with shell holes. I could see a number of dead horses stretched out on the roadside.

They were from a mountain battery which had crossed just at daybreak. Not a living thing was visible---indeed, nothing could possibly live in that welter of flying shell fragments.

We stopped our horses and surveyed the lane of death over which we had to pass to reach the other side.

"Do you think we can make it, Metia?" I asked.

His face was dead white and his jaw set.

"We have to make it!" he answered grimly.

We could perhaps have walked it in greater safety, but the commander had ordered us to hurry and I decided to take it at a gallop and take a chance. The five ambulances and the supply wagon drove up and I ordered them to wait until we reached the other side.

"When I wave my handkerchief from the edge of the woods on the sand-hills," I commanded, "whip up your horses and come over at a gallop. Scatter out well and, if any one is hit, stop and pick him up and bring him with you but let the horse and ambulance remain."

"Tak tochena! (Yes, surely)" they replied in chorus; and that was always the way when told to do anything---no matter how impossible the task might seem.

We gave our ponies the spurs and started across. We bent low in the saddle, and the torn surface of the road seemed simply to fly by as our ponies, excited by the scream of the shell and the crashing explosions, lengthened their stride.

We were a quarter of the way across when my pony suddenly braced his feet under him, slid a few yards and came to a dead stop, almost throwing me over his head, so sudden was the movement. Metia reined in his horse, narrowly missing running me down. My pony was now rearing, his front feet pawing the air. He tried to turn back but I plied the spurs and whipped him cruelly with my Cossack knout.

I saw now what the trouble was. Lying on the side of the road was a dead artillery horse, his feet sticking out in the road, and my pony was afraid to pass him. He snorted and shied as the shells burst unpleasantly near him with loud reports and the air hummed with deadly flying fragments. I shouted to Metia to ride on, thinking that if my horse saw the other one go by the dead animal he would follow. Metia dashed ahead, and after spurring and beating him my pony followed.

We thundered over the first bridge. The second bridge had been hit by a shell and some engineers who had been lying under cover of the embankment were busy repairing it. We crossed the third bridge and finally galloped into the protecting grove of trees, and I rode back to the edge of the wood to a high ridge where I could be seen by our drivers on the other side and waved a handkerchief in the air. As I had half suspected, the thing had really looked worse from the other end of the road than it really was, for the shells were not so close together as they appeared to be.

After a few minutes I saw the ambulances shoot out of the forest and start across the road, the horses galloping and the dust flying.

Everything went well until they were half-way across. Then apparently they were seen by the Austro-German observers, for I saw the yellow-white puff of shrapnel directly above them. The second ambulance veered to the side of the road, the horse stumbling and falling, and the ambulance overturned. The driver was thrown out in the middle of the road and lay, a little inert spot, on the brown surface of the road. The ambulance immediately in back of him stopped and I saw the driver leap out, gather his fallen companion in his arms, place him in the ambulance, leap back on the driver's seat and whip up his horse.

The Germans continued to rain shrapnel down on them, but were timing their shells badly, so that they burst beyond the road and the remainder of the party reached the sheltering growth of trees in safety. I found that the driver had been struck in the shoulder by a shrapnel ball which passed through downward and forward, emerging from his chest just below the collar-bone. We hastily bound him up, put him in the ambulance, and went on. The road was fairly well screened by trees and we were able to reach our troops, who were occupying the captured third line of Austrian trenches.

Leaving the ambulances under some trees, I started for these trenches just as our soldiers left them in another attack against the Austro-Germans, who were desperately endeavoring to defend a small village which had been partly destroyed by our artillery.

They had numerous machine-gun emplacements and strong dug-outs in this village, but our troops, although they lost heavily, were able to force them out. I could see them advancing beyond the village after a few moments of sharp fighting. If they drove the Austro-Germans back far enough I saw that this village would make an ideal location for an advanced dressing station, so I cautiously followed up on foot toward the village.

Wounded Austrians, Germans and Russians lay sprawled on the ground together, and a great many dead on both sides were scattered thickly about. The village was a tumbled mass of ruins, part of which was still smoking from the recent fire caused by our artillery.

I noticed the entrance to a large dug-out along the edge of the village. Several telephone wires, which the Germans had not had time to remove, led down into it. I decided it would make an excellent dressing station, for it had thick walls and would stand heavy shelling.

Before I went down the steps I examined my revolver, as I had no hand-grenades with me and I recalled a similar experience I had had early in my trench-warfare adventures.

The dug-out was dark and as I entered I could just make out a rough table littered with papers. Then there was a sudden stabbing flash of light from the side, the sharp crack of a revolver, and I felt a stinging pain in my abdomen. With the flash, I fired, blindly aiming at the direction from which it had come, leaning partly over the table to do so, and jumped back from the door.

I felt weak and giddy, and beads of perspiration were on my forehead. I unloosened my clothing and found that the bullet which had struck me had just grazed the skin, producing a red wheal across my abdomen. In the language of the old hunters of central Pennsylvania, I had been "scutched."

I sat down on one of the steps to regain my composure. As I had leaped back through the door I had heard something metallic clatter to the floor of the dug-out and now I could hear a shuffling and the sound of labored breathing coming from inside. Then I heard a drip, drip, drip, as though water was spilling from some overturned vessel on to the floor of the dug-out. I waited possibly five minutes and then, still holding my revolver, I peered into the dark interior. As my eyes became accustomed to the gloom I saw a man in the gray uniform of Germany seated on a bench beside the table. He was leaning back, his head resting against the wall and turned to one side. As he did not move I stepped into the dug-out and, pointing my revolver at him, walked over and pushed him on the shoulder. He slid limply off the side of the bench, his body resting against its arm.

Blood was flowing from a wound in his left chest just above the heart and, running down over the bench and dropping to the floor, had produced the sound which I had heard. On the floor lay the latest type of German automatic revolver. By his uniform I saw that he was an under-officer, and when I came to examine him I found that he had a slight wound from a bullet through the left arm.

I had killed him with my first shot, merely by chance, for I did not see him and only fired at the flash of his gun.

In discussing the incident later with the commander of the regiment, he told me that the German officers had told their men that the Russians were attacking with Cossacks who, when they took prisoners, always cut their tongues out and their ears off, and this under-officer, having been wounded and fearing capture, had evidently decided to sell his life as dearly as possible when he saw me enter the dug-out, rather than be captured.

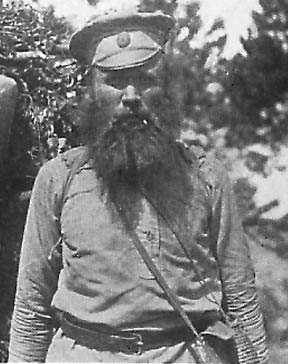

Fig 23. Orderly

who rescued a wounded man who lay for five days under the German barbed

wire. This old Russian specialized in rescuing wounded from under the Germans'

noses.

Fig. 24. Shot

through the lung, this wounded Russian soldier lay for five days under the

German barbed wire not 40 feet from their trenches. He begged them to shoot

him or take him in, but they refused, allowing him to lie there without

food or water. He was rescued in broad daylight by the bearded orderly in

the background, who crawled through the marsh grasses and dragged him back

to the Russian lines.

We established our advanced dressing station in the dug-out and proceeded to take care of the wounded Germans and Russians. Our lines had been advanced another mile beyond the village and here, encountering strong resistance, our men had dug themselves in.

We remained in this situation for ten days, during which the enemy made eleven desperate counter-attacks, but they were unable to break through.

It was an extremely difficult task to get our wounded back over the road across the marsh. We could send them only at night, for the Germans, although they could plainly distinguish the Red Cross on the side of our ambulances, never lost an opportunity to pour a terrific fire on the wounded-laden carts.

The German system of shelling Red Cross dressing stations and ambulance columns and firing on the wounded as they crawl back to their lines is to my mind one of the significant things of this war.

Were it done by a savage, unlearned people such as the wild African, one could understand it, but when ordered by the highest officials of a so-called Kultured race it points out with startling vividness the great menace which threatens the civilized world. It has a very distinct object: namely, to instil into the minds of our peasant soldier an absolute loathing and horror of the war---in other words, to break his morale.

Whether it will accomplish its purpose I cannot say, but it surely will show dearly to all thinking people that the Potsdam ring must be broken. Germany must not, shall not, win this war!

Chapter Twenty-Two: A blind army.