Zap Comix's first printer on R. Crumb:Curled in Characterby outlaw poet Charley Plymell

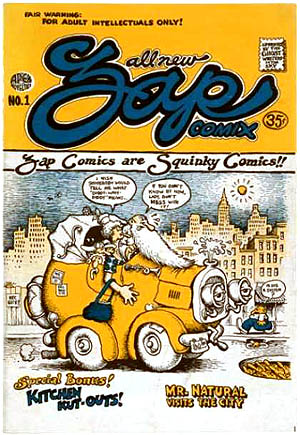

My favorite reality chamber in the '40s and '50s was to cradle myself in the big overstuffed armchair with a stack of comics on the floor and some beside me in the chair a smorgasbord of preferences that would satisfy a reading orgy should I decide to shift quickly from Mary Jane and Sniffles, the first "Lucy in the sky with diamonds" (or dust she sniffed), to Prune Face, The Submariner, Scarecrow--or the old standbys--Captain Marvel, Batman and his Robin, et. al. I might have just traded for some more esoteric ones, "The Thing," a Luftwaffe pilot who went down in the swamp and turned into a swamp monster trying always to resolve his identity, Or "He-She," who turned sideways to foil the police with its sex. One side was a man, one a woman; the first hermaphrodite androgynous transvestite character, who, I'm sure could enjoy great popularity now. The classics would be shuffled to the bottom of the pile; I would put my classic education off as long as possible; however, they were still better to get into than reading the stilted, pretentious English of James Fenimore Cooper. Oh yeah, and there were ones I never could get the plot, like Little Orphan Annie and Prince Valiant--they were also towards the bottom of the stack. I'd read Bugs Bunny first, or other Disney characters. It wasn't until much later in my scholarly pursuits that I found a couple of references to the metaphysical aspect of Disney by none other than Ezra Pound, who thought Disney was one the greatest metaphysician of the 20th century, who brought us a personified natural world -- pretty heavy stuff indeed! The smell of colored ink and newsprint was an aroma that lured me into the page. As important to me as the stories, were the characters, who were not remote, and certain frames I had to go back to and curl up with a while, dwell on, until I absorbed the full action and context. In this aesthetic, the comics seemed more like movies to me than a textual stories. I would imagine getting the characters into a story line would be the most difficult aspect of cartooning. Our linear-literary consciousness culture always wants "the story". There is something also about cartoons that to me had an affinity to old radio shows, which may be just a generational personal feeling rather than an aesthetic, implicit in the art form. Sometimes I would trade for a little fat book made to flip the pages and make the characters move, which is the basis of filmed cartoons. I have regrettably not yet seen any of R. Crumb's film work by or about him. Among other delights, it was the creation of characters that grabbed me into Crumb's work. Theorizing, in hindsight, those I selected to keep on the top of the pile would have the necessary values that belong to the art; be profane, carnival, or vulgar in the artistic sense. Crumb filled those criteria. His good invention of character, most often himself, and the marvelous idiolects that was not afraid of controversial dialog also set a fearless tone that could go back in traditional literature to Chaucer. He was in the generation of cartoonists with a message, and his characters brought a larger "character' to the form, a whiff of genius, compared to the piddling, politico-socio-culture engineering that steers our categories today: feminist, multicultural, new age, and all that which sadly seems to complicate our national character in divisiveness, convolution, complexity and more control. Ironically, most older comics were pretty one-dimensional, or highly skilled in converting any message into acceptable story lines. Obviously Dick Tracy was not a Dick for nothing and was no doubt one of J. Edgar's favorites, tucked in among his confiscated erotic reading material. Comics like American Heroes had the simplest story lines though others like Batman and Robin, simple in their ethos, good over bad, had a particular subliminal psychological undertone that has something to do with their lasting popularity. Crumb is also literary, evidenced in all his work, even in his secondary scholarly creations like his masterful work on Kafka. He certainly should be taken seriously as one of the masters in all cartoon history, not just "underground", (if that designation has not outlived its usage). I remember two comics I bought in a trunk in Kansas at an auction in town ready to be cleared for a lake and dam, incidentally, where Bill Burroughs now goes trap shooting. One was The Katzenjammer Kids, and the other was Andy Gump. They had cardboard covers and the format was almost square, printed on newsprint, with introductions written by famous people such as Mayor LaGuardia and Enrico Caruso. There has always been a sustained audience for Comics, and there is a surprisingly large audience for "underground comics", which I'll talk about later, but the quality of consciousness in underground comix contains a certain realism that still has to be disguised in the mainstream. Think how many high school kids would stay in school if they had these cartoons for their curricula, instead of the most deadly boring sanctified official governmental socio-soft-Fascism that cleverly and constantly engineers our brains and controls our movements to become economic and cultural slaves to their empires. I haven't followed the New York mainstream press stories and the recent controversy over Crumb's work, but I'm sure it exemplifies what I'm talking about. As our society swells, it divides, and that division is engineered into the mainstream from diversity. In the "doublethinktank," these actions have the counter-effect of creating more identification and control. The boomers and their babes have to have these markers to know the good guys from the bad guys; freedom of speech is too simple for them (or too complex). One could stand back and watch it happen from a distance; certainly other countries have a different perspective of this country, but I'm still foolish enough to hope that all the cartoonists and their audiences will continue to enjoy freedom, liberty, justice, sex and deprivation as is tradition. But as we see in today's politics, depicting these historical themes is interpreted as causing the vulgarity it displays. There°s no tolerance for exaggerating fat asses in our society, so if the Organization of Fat Asses can make the government engineer them into a non-discriminatory categorical squeeze in the control box, everything will be right. Oh Yeah. I think the first strip of Crumb's I saw was in an underground newspaper from the upper Midwest. There were some poets from Cleveland associated with the poet, d. a. levy, who had come to the San Francisco scene during the mid Haight-Ashbury and who had given me a paper. I had a larger press in the Mission District at the time. I liked the posters in the head shops that were thriving in the Haight. I didn't care for the religious and flower-power drawings in the Oracle, so I put out a couple of issues of a newspaper I called The Last Times in which I lifted Crumb's strip from the Midwest underground paper. There was a need for more newspapers that the street kids could hawk, so someone was there buying all I could print, which was only a paltry 500 or so copies. I never made any money on them. There is only one person I know who has copies of the papers. I assumed most of them were tossed. I thought they were more exciting than the Oracle, but what did I know. Anyway, poster art was going to dominate the paper scene for a while. I was into the literary and later the music scene at the time Crumb came to San Francisco and I had kept an old pre-war Multilith and offset camera from the Mission shop. We were having nude parties at the Post Street address from the Gough Street scene which had disolved. We had complimentary tickets to the Janis Joplin and Big Brother concert, but we were too stoned to get there, though it was only a few blocks. Lots of people dropped by, someone talked about a new group he was involved with called "Pink Floyd". Billy Jharmark of the Batman Gallery, who later gave me his 52 MGTD Classic, and his friend, Bob Branaman who was living in the backseat of his '49 Chevy were still on the scene. Even Huncke visited us at that pad, and we associated him with the disappearance of an IBM Selectric, bless his heart. There was junk on the street and pot in the cupboard. Bob Branaman was a "finder"; he eventually turned up everyone who was anyone. It was a business deal, or as close as one could come to it that brought Don Donahue to the door. It was supposed to be 5,000 copies, but that's a stretch. I'll tell you why. But first -- I loved the drawings Don laid out on the desk. I felt like I was curled up again in that chair and knew that these drawings were important artworks, so I wanted to be identified as the printer, and thus put my name on the bottom of the back cover. It is amazing just much the printing technologies have change just from the Sixties, and of course, we had pre-war equipment, that wasn't really capable of a printing job like Zap Comix. I would have to make the Multilith dance and sing; I took on the job. After all, I was arrested for forgery and uttering when I knew Branaman in the Wichita County Jail. But it was the lack of technology which caused most of the waste in run of what was supposed to be 5,000 copies...my guess is around 1,500 copies. My wife, Pam says less. I don't think my printers scruples would allow too much of a rip-off, but most everyone was on acid or pot and was so excited to see the finished copy, and since there was little money and barter involved, I don't know who counted. Prior to that meeting, I had been attending parties at Don Allen's, the West Coast editor for Grove. I was trying to get both him and Ferlinghetti to publish Crumb and was also working toward getting Keep on Trucking drawings off Crumb. The literary publishers seemed uninterested at the time, even though I was later paid well ($300 plus) a piece for a couple of poems that were illustrated in Evergreen Review by artists I never knew; I tried to introduce publishers to Crumb, but they had other interests (or tastes). I explained to Don Donahue that I really needed a chain delivery on the press, which only had a small chute for 500 sheets, and a spray attachment to powder the paper so the colors wouldn't offset on the next sheet. We pulled out small stacks from the chute as I squirted each of the sheets with powder from a turkey baster. The chain-delivery, incidentally was invented by a printer in San Francisco as a Rube Goldberg devise to grip the sheets of paper and stack them in a receding pile (funny how the Multilith Company didn't think of it). Anyway, the chute delivery had to have two little chrome wheels that ran along the edge of coated cover stock (which in itself was stressing the press's capability). An the images, which by now I had gone over with Don, sending him back to Crumb to make separate color overlays (continuous tone was out of the question). Which maxed out the 10xl5 format of the press. In other words there was no margin for the wheels to carry, that didn't contain an image. I solved that problem by soaking cotton pads in the water solution and attaching them to the wheels' fixtures with a rubber band. Mind you, all the sheets of cover stock had to be run through the press four times, for each color, including the black. And registration had to be perfect, so I ran some trial pages with black only, first as a template for all the other colors because I wanted to put on the black last to cover any gap in the registration. In addition, the Multi had to be fine-tuned constantly to hold its register. Even at that, every 10 or so copies the lines would jump out of register a little. This was characteristic for most all machines at the time. I also had to compensate for slight differences in the stock trim, because Don bought it at surplus odd lot paper dealer, and it may have been cut cross-grained or absorbed humidity before the next run. The technical problems were endless. The format remained the same for many years in the Comix trade, but it was in a sense arbitrary, because it was the maximum size for a Multilith 1250. I liked the newsprint, because it was like the old 1917, 1920 editions I mentioned earlier. I forget whose idea it was, probably mine to put the inside on cheap newsprint, which had been used also in some very fine little press poetry books I had from France. But the newsprint was no picnic to run, either, usually newsprint was made for a web press that took it in rolls. It didn't cut out and run as well as #20 bond or book stock. Anyway we completed the job and went to Crumb's apt. for a party. We got high and drank and ate cake. I especially remember his overstuffed armchairs and his old Philco radios. Anyway, the collector's item, "printed by Charles Plymell" is well worth its price; I'm pretty sure the original count was short. The last time I saw one was one I had given a friend's kid who lived on the Bowery. He used to take it down to the Bat Cave in the city and watch its value climb. Its was with some gallows humor that I traded the press to Don, and told him that he could learn printing as well. The darkness compounded when I saw the chaotic struggle of old wiring and mattresses and paper all over the place in his ghetto warehouse. I told him he could expect some waste. He fought it to its end in Great Balls of Fire. It took courage for me to enter the premises, and knowing all the complications that vex an experienced printer, I looked with sympathy at that chaotic scene, but he excelled in chaos. It serve him well. A true Man of the Comix. It was many years later, while I was living in Cherry Valley, NY, that S. Clay sent word of a Comix show in the city. I hadn't seen Crumb since the first Zap, nor S. Clay since I printed his first folio on Grist's press when I was working at the Campbell's Pork & Bean factory in Lawrence, KS. The plan to go to this show began the strange comixesque episode in Cherry Valley with a local character straight out of a 60's cartoon, a 70's comic fan, mechanic, dreamer, "Dangerous Dan" his friend, Ray, Mike, myself and Melodie. Ray had an old four-door Caddy with a Bat signal painted on the back (he went in for a revival fad at the time). The line at the gallery was several blocks long. I caught a glimpse of artist Spain Rodriguez, who got us in, but it was packed so much I couldn't get to Clay. Crumb came out and was talking to Allen Ginsberg. I tried for a photo but the camera lens was all wet from sweat and humidity in the gallery. I gave it to Melodie who tried to get some shots. I groveled my way through to Crumb to say hello and talked to Ginsberg for a while. People started asking me for my autograph and took pictures I've never seen. Ginsberg turned to me and gestured to the packed gallery and said "See what you started." The rest of the evening was trying to press in to see S. Clay, but we had to leave. On the way home we were stopped by New Jersey troopers who demanded Ray, in his baseball cap get out of the car; he handed them a temporary license, which made the trooper say "What's this, your kindergarten report card?" One by one we filed out of the car while they searched the trunk. They were sure they had something...but WHAT? Finally, I, an old white bearded man wearing a handkerchief around my head, got out and told the troopers that I was from a small village which didn't have many resources and Ray was they only Limo driver I could find. They sensed the paper work would be too much on this scene, so they just told us to keep on going...out of New Jersey. There was a lot more to that cartoon, but it will have to wait. It does seem though that reality takes on a special nearness when it is near a comic event. In science, it would be called a cosmic event. I hear that Crumb got some heat from the multicultural fems about ladies with

the big butts and the likes. He has chosen to live in France. I think that's a

good idea. The best way to really see this country crumble, if it isn't in a

cartoon, may be from far away. |